Working with signal constraints for epidural speech BCIs

All high-performance speech BCIs share a common feature: they place electrodes either directly on the brain surface (subdural) or penetrating into cortical tissue (intracortical). Both approaches require opening the dura mater, the tough membrane surrounding the brain, creating risks of infection, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, and chronic inflammatory responses at the neural interface.

Epidural placement, positioning electrodes above the intact dura, offering a theoretically safer alternative. The dura remains closed, eliminating direct brain contact and substantially reducing infection risk. No glial scarring occurs in brain parenchyma. For healthy human trials or widespread clinical deployment, this safety profile is compelling.

The fundamental question is whether epidural recording can capture the neural signals that speech decoding requires. The answer is not straightforward, because speech BCIs depend critically on high-gamma activity (70-170 Hz) and high-frequency neural signals face compounding physical constraints that lower frequencies do not.

It should be noted before we proceed that, despite research showing functionally negligible differences between epidural and subdural macro-ECoG for BCI applications, and despite successful demonstrations of epidural motor BCIs in humans, this implant placement has not been tested for speech decoding. Every successful speech BCI to date has used subdural or intracortical electrodes.

The purpose of this article is to examine whether epidural recording can meet the specific demands of speech.

The Triple Penalty in Epidural Speech Decoding

Three independent factors combine to make high-gamma recording through the dura particularly challenging:

1. The 1/f power law

Neural signals follow a characteristic frequency distribution where power decreases as frequency increases. High-gamma activity is inherently low amplitude compared to slower rhythms.

2. Dura attenuation

The dura mater acts as a low-pass filter, attenuating high frequencies more than low frequencies. This attenuation compounds the already-low amplitude of high-gamma signals.

3. Inner speech amplitude

For applications decoding imagined or inner speech rather than attempted speech, the neural modulation is approximately 52% of attempted speech amplitude (Kunz et al., 2025), further reducing an already-attenuated signal.

Whether epidural macro-ECoG can overcome this triple penalty to achieve adequate signal-to-noise ratio for speech decoding remains an open empirical question.

In the following section, I will briefly examine the physics of neural signal recording from first principles to illuminate the challenges.

Fundamentals

Decomposing Neural Signals with Fourier Analysis

To understand why high-frequency neural signals pose unique challenges, we must first understand how complex signals are analyzed.

Fourier analysis is the mathematical technique that decomposes any time-varying signal into its constituent frequency components, doing mathematically what your cochlea does physically. It takes a complex waveform and reveals the individual frequencies that compose it.

Consider the following analogy. When a pianist plays a C major chord, three notes sound simultaneously - C (261 Hz), E (330 Hz), and G (392 Hz). What reaches your eardrum is a single complex pressure wave, the sum of all three frequencies. Your cochlea physically separates these frequencies, allowing you to perceive the individual notes.

Neural signals recorded from the cortex are similarly complex. At any moment, the voltage measured by an electrode reflects the superposition of oscillations at many frequencies...

- delta (1-4 Hz)

- theta (4-8 Hz)

- alpha (8-12 Hz)

- beta (13-30 Hz)

- gamma (30+ Hz)

...plus broadband activity that spans multiple frequency ranges. The Fourier transform converts this time-domain signal (voltage versus time) into a frequency-domain representation (power versus frequency).

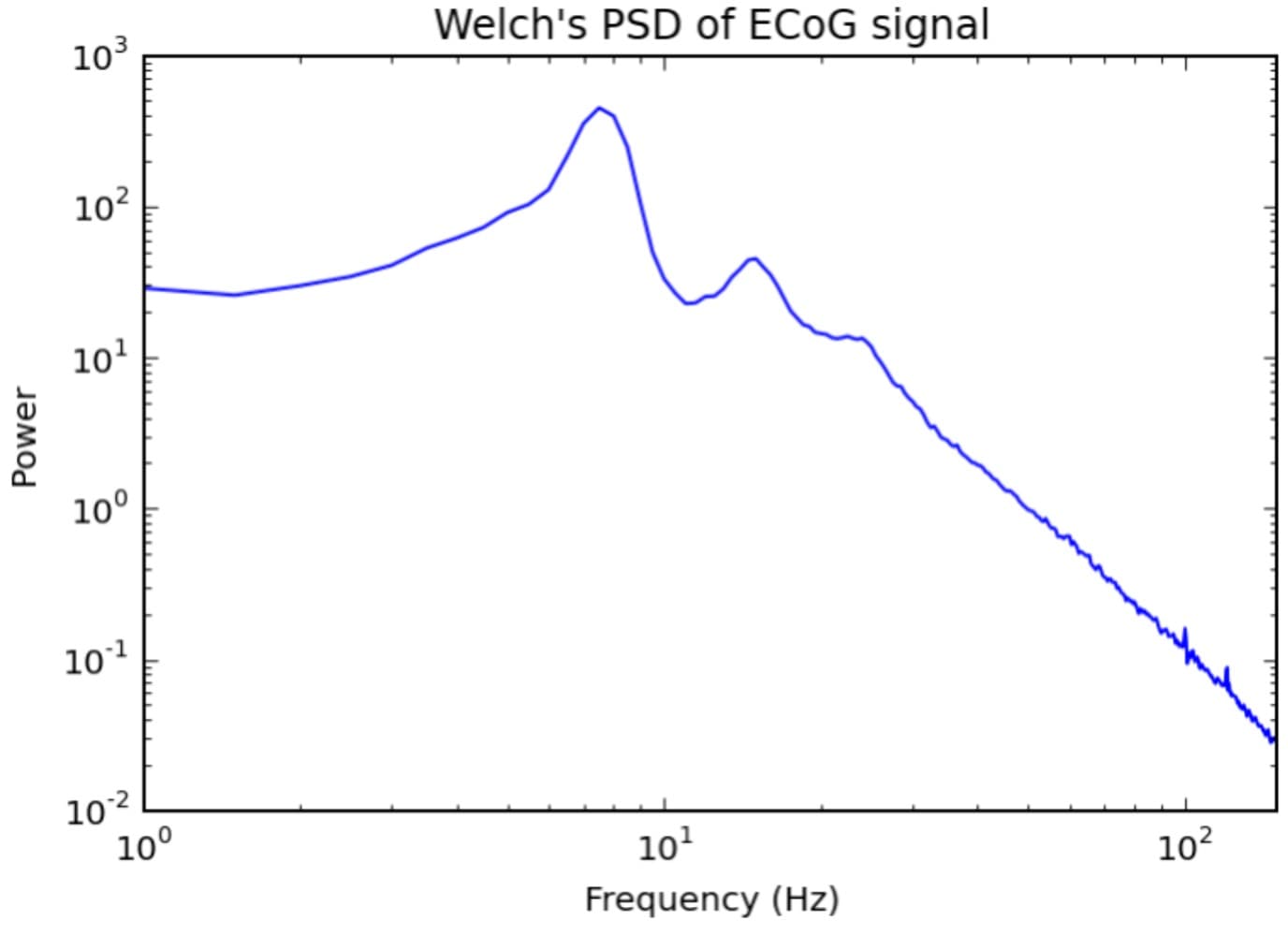

The output of this transformation is the Power Spectral Density (PSD), which shows how signal energy is distributed across frequencies. On a PSD plot, the x-axis represents frequency (in Hz), and the y-axis represents power (typically in μV²/Hz or decibels). Peaks in the PSD indicate rhythmic activity at specific frequencies; the overall slope reveals the structure of neural activity, and flat regions indicate where neural signal has fallen below the noise floor.

Understanding the 1/f Power Law

When you plot the PSD of neural recordings on logarithmic axes, a pattern emerges. Power decreases approximately linearly with increasing frequency. This relationship, known as the 1/f power law, is expressed mathematically as:

where typically ranges from 1 to 3.

This means that neural signals at 100 Hz have substantially less power than signals at 10 Hz, which in turn have less power than signals at 1 Hz. On a log-log plot of the PSD, this relationship appears as a straight line with negative slope.

Why does this happen? The answer lies in the biophysics of neural tissue. Slow fluctuations in the local field potential involve large populations of neurons synchronizing their activity over longer timescales. When millions of neurons in a cortical region shift their membrane potentials together over hundreds of milliseconds, the resulting voltage change is substantial. Fast fluctuations, by contrast, involve smaller, more local ensembles of neurons and occur over shorter timescales. The spatial averaging inherent in extracellular recording means these rapid, localized changes produce smaller voltage deflections at the electrode.

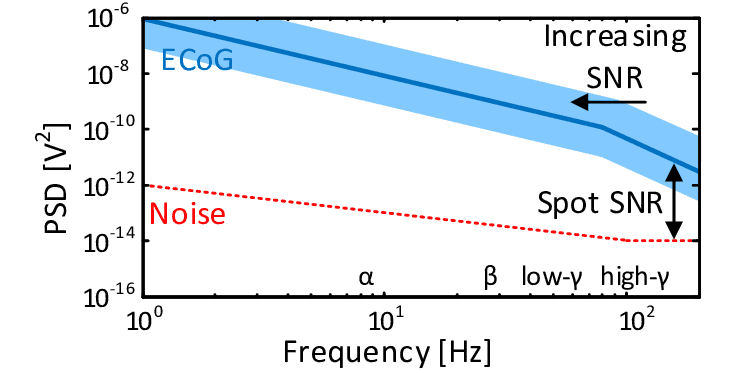

The slope of the 1/f curve (the exponent β) changes with brain state, age, and neurological disease, making it a subject of active research. For our purposes, the critical implication is that high-gamma activity (70-170 Hz) is inherently low amplitude compared to lower-frequency oscillations, regardless of recording technique.

The Noise Floor

Every recording system has a noise floor, which is the level below which signals cannot be distinguished from electronic fluctuations. Understanding the noise floor is essential for neural recording because it determines which frequency components can actually be measured.

On a PSD plot of neural activity, the noise floor appears as a flat horizontal region at higher frequencies. Below this region, the PSD follows the characteristic 1/f slope - this is real brain activity. Above this region, the PSD flattens out - this is electronic noise from the amplifier and electrode, independent of what the brain is doing.

The frequency at which the declining neural signal intersects the flat noise floor is the effective bandwidth of the recording. This is the highest frequency at which neural activity can be reliably detected. For an electrode with a noise floor at 100 Hz, no neural activity above 100 Hz can be measured because the signal is drowned in noise.

For speech BCIs, this creates a critical threshold. Speech decoding depends on high-gamma activity in the 70-170 Hz range. If an epidural recording system hits its noise floor at 100 Hz, more than half of the high-gamma band is inaccessible. The entire frequency range that speech BCIs rely upon would be lost.

Determinants of Electronic Noise

The noise floor is not a fixed property. It depends on multiple factors in the recording chain that can be engineered. Understanding these factors reveals pathways for optimization.

Electrode Impedance

The impedance of the electrode-electrolyte interface determines how efficiently neural voltages transfer to the amplifier. Higher impedance means greater thermal noise and greater signal attenuation through voltage divider effects.

The Johnson-Nyquist relationship shows noise voltage scales with √R according to the following formula:

The most direct way to reduce impedance is to increase electrode surface area. The relationship is straightforward: at the electrode-tissue interface, a capacitive double layer forms. Larger surface area means more capacitance. And impedance is inversely proportional to capacitance:

where is the imaginary unit (don't ask - it's a mathematical trick for tracking signals that oscillate and shift in phase), is the angular frequency, and is capacitance. More surface area → more capacitance → lower impedance. This is why low-impedance electrodes are desirable for neural recording.

For electrode engineering, what matters is electrochemical surface area, not geometric footprint. A 25 mm diameter electrode with a smooth surface has far less electrochemical surface area than a 5 mm electrode with a highly porous or nanostructured surface. Increasing effective surface area through coatings and texturing, without increasing the electrode's physical dimensions, preserves spatial resolution while reducing impedance.

For planar electrodes, impedance is typically assumed to scale inversely with area (). However, recent work shows that for platinum electrodes, 1 kHz impedance transitions from area scaling () to perimeter scaling () when electrode radius falls below approximately 10 μm (Cogan et al., 2022). This transition occurs because diffusion-limited processes at the electrode surface shift from planar to spherical diffusion behaviour. The practical implication is that very small electrodes with pseudo-capacitive coatings can be made smaller than area-scaling would predict before thermal noise becomes limiting.

Surface coatings

Several coating materials have been demonstrated to dramatically reduce electrode impedance by increasing effective electrochemical surface area without changing geometric footprint:

PEDOT:PSS

PEDOT:PSS (poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate)) is a conducting polymer that provides both electronic and ionic conductance. I'll write a separate article on PEDOT:PSS because I love its chemistry so much - the short of it is that it's a conjugated polymer, which is a plastic with alternating single and double carbon bonds, which creates a channel for electrons to flow through.

The porous, rough surface of the PEDOT:PSS structure also creates large effective surface area. Electrochemical deposition of PEDOT:PSS can reduce interfacial impedance by up to 90% compared to bare metal electrodes (Saurav et al., 2025). One study found PEDOT:PSS coating decreased impedance by almost two orders of magnitude compared to uncoated metal electrodes (Bianchi et al., 2022). For 12 μm diameter electrode sites, PEDOT:PSS achieved 37 ± 2.6 kΩ at 1 kHz, the lowest of all materials tested (Lewis et al., 2024).

However, the long-term stability of PEDOT:PSS remains a concern. As a mixed ionic-electronic conductor, when voltage is applied to PEDOT:PSS, ions from the electrolyte move in and out of the polymer matrix - this is actually how it stores charge. But ion movement causes the polymer to physically swell (ions in) and contract (ions out). The problem is that the metal substrate doesn't move. So you have:

- Repeated volume change: Each stimulation pulse causes the polymer to expand and contract while the metal stays rigid. This creates shear stress at the interface, like two materials with different thermal expansion coefficients being heated and cooled.

- Higher voltage = more extreme swelling: Larger voltage excursions drive more ions in and out per cycle, meaning more extreme volume changes, meaning more mechanical stress per pulse.

- Fatigue accumulates: Over millions of cycles, the repeated stress causes cracks to nucleate and propagate through the film, and the interface eventually fails.

Additionally, if voltage excursions exceed the electrochemical stability window, you can get water hydrolysis (producing gas bubbles that physically push the coating off) or corrosion of the underlying metal.

Thin coatings (<300 nm) fail at relatively low cycle counts, with one study observing failure at fewer than 25,000 stimulation pulses (Cuttaz et al., 2022).

Thicker coatings fare better because higher capacitance means lower voltage excursions during stimulation - the charge is spread over more material, reducing electrochemical stress at the metal-polymer interface. PEDOT:PSS on gold electrodes showed marginal impedance changes after 7 weeks of continuous pulsing, corresponding to over 4.2 billion bipolar current pulses (Boehler et al., 2020).

The failure mode typically begins with cracking, followed by delamination from the underlying metal substrate. Several strategies can improve adhesion: roughening the metal surface before coating, using chemical cross-linkers such as GOPS (3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane), or employing sputtered iridium oxide as an adhesion layer (Cuttaz et al., 2022) (Oldroyd & Malliaras, 2023). Notably, in accelerated aging studies, pristine PEDOT:PSS electrodes (where PEDOT:PSS is the electrode material itself, not a coating on metal) showed higher stability than PEDOT:PSS-coated metal electrodes, suggesting that the metal-polymer interface is often the weak point (Oldroyd & Malliaras, 2023). Metal-free PEDOT:PSS electrodes remain largely a research-stage approach, but the finding points toward future design strategies.

Iridium oxide

Iridium oxide (IrOx), particularly sputtered iridium oxide film (SIROF), achieves low impedance through two mechanisms.

First, the sputtering process creates a nanostructured surface - densely packed nodules approximately 200–400 nm in diameter that increase effective surface area (Cogan, 2008). This morphology is tunable; adjusting oxygen flow during deposition can yield microporous films with highly extended fractal surfaces.

Second, unlike purely capacitive materials, iridium oxide undergoes reversible faradaic reactions (Ir³⁺ ↔ Ir⁴⁺), providing an additional charge transfer pathway beyond double-layer capacitance. This combination of high surface area and electrochemical activity gives SIROF both low impedance and high charge storage capacity.

SIROF is the coating of choice for Blackrock Neurotech's Utah arrays, the most widely implanted intracortical electrode in human BCI research. On these arrays, SIROF achieved average impedance of 6 kΩ at 1 kHz compared to 125 kΩ for platinum - a 20-fold reduction (Negi et al., 2010). SIROF electrodes on 12 μm sites achieved 70 ± 9.7 kΩ at 1 kHz (Lewis et al., 2024). Films exceeding 1000 nm thickness have been deposited without stress-induced delamination, and cathodal charge storage capacities above 100 mC/cm² have been demonstrated (Cogan, 2008).

Nanostructured noble metals

Nanostructured noble metals achieve low impedance through morphological manipulation rather than coating with different materials.

Platinum black, deposited electrochemically, creates a high-surface-area fractal morphology consisting of interconnected platinum crystals approximately 5-10 nm in diameter that form a porous, "cauliflower-like" network. This nanostructure provides enormous electrochemical surface area, typically 20-40 m²/g with roughness factors around 23, enabling dramatic impedance reduction. Total impedance at 10 Hz dropped from 36 kΩ for uncoated platinum to 6 kΩ for platinum black, a six-fold reduction (Qiang et al., 2025). The porous architecture also increases charge storage capacity by providing vastly more surface area for double-layer capacitance.

However, the same structural features that enable platinum black's electrochemical advantages create severe mechanical vulnerability. The porous structure is vulnerable to external stimuli and destroyed easily (Kim & Nam, 2013). The delicate interconnections between nanoscale platinum grains lack structural integrity, and weak adhesion to the underlying substrate compounds the problem.

Failure mechanisms. Platinum black coatings fail through several interrelated pathways:

- Shear stress during insertion: Electrode insertion into neural tissue generates shear forces at the coating-substrate interface. This is of particular concern during electrode insertion, resulting in shear stress and potential removal of the platinum black (Harris et al., 2025). The porous coating structure provides limited resistance to tangential forces.

- Poor substrate adhesion: Platinum black does not form strong chemical bonds with many substrates. Studies have shown platinum adheres poorly to silicon oxide and stoichiometric silicon nitride because local interfacial reactions do not occur. The coating-substrate interface becomes the primary failure point rather than cohesive failure within the coating itself.

- Mechanical fragility under agitation: Accelerated stress testing reveals the coating's vulnerability dramatically. Standard electroplated platinum black loses more than 80% of its coating under ultrasound cleaning, while coatings deposited under ultrasonic agitation ("sonicoplating") lose only 2.5% under identical conditions (Ferguson et al., 2010). This order-of-magnitude difference demonstrates how deposition method affects mechanical robustness.

- In vivo degradation: Beyond acute mechanical failure, platinum black is mechanically fragile and degradable in the physiological environment (Yin et al., 2021). Chronic exposure to biological fluids and tissue micromotion progressively degrades coating integrity.

Quantitative shear stress data is notably absent from the literature. Unlike industrial coatings that undergo standardized pull-off (ASTM D4541) or lap shear testing reported in MPa, neural electrode coatings are typically characterized through ultrasonication survival, tape peel tests, and electrochemical stability (impedance/CSC changes after stress). No studies have reported critical shear stress thresholds for platinum black failure, making it difficult to establish engineering design margins for electrode insertion forces.

Mitigation strategies have been developed to improve platinum black durability:

-

Sonicoplating: Electrodeposition under ultrasonic agitation (40 kHz, ~276 W) produces denser, more uniform coatings with dramatically improved adhesion. Sonicoplated coatings exhibit 6× larger electrochemical surface area than conventional DC-plated counterparts, with coating survival improving from ~20% to ~97.5% under standardized ultrasonication (Ferguson et al., 2010).

-

Adhesion-promoting interlayers: Depositing a "fuzzy gold" intermediate layer before platinum black electroplating provides better mechanical anchoring. The textured gold surface increases contact area with the platinum black, and fuzzy gold interlayered coatings maintained 77% of their effective surface area after stress testing compared to lower retention for directly deposited coatings.

-

Polydopamine adhesive: Drawing inspiration from mussel adhesion chemistry, polydopamine layers electrodeposited between platinum black structures substantially improve mechanical stability. Polydopamine-modified electrodes retain their initial impedance values after ultrasonication that causes dramatic impedance increases in unmodified platinum black electrodes (Kim & Nam, 2013).

-

Double-layer coatings: Combining platinum black with conducting polymers (Pt-PP: platinum black + PEDOT:PSS) leverages the complementary properties of both materials. The platinum black provides high surface area while the polymer layer improves adhesion and electrochemical stability. These double-layer coatings show no significant change in charge storage capacity after 2,500 CV cycles, and the mechanical and electrochemical stability has been verified by both ultrasonication and cycling stress tests (Wang et al., 2019).

Cytotoxicity concerns compound platinum black's limitations. Traditional electroplating solutions contain lead acetate to improve nucleation and coating adhesion. DNA synthesis of rat oligodendrocytes was inhibited when exposed to platinum black extract, possibly due to lead release (Yin et al., 2021). Lead-free alternatives including "platinum gray" have been developed and applied to retinal prostheses, though they typically produce coatings with somewhat lower surface area.

Nanoporous gold, created by dealloying gold-silver alloys, achieves approximately 30 kΩ at 1 kHz (Seker et al., 2009). The dealloying process, selectively dissolving silver from a gold-silver alloy, leaves behind a bicontinuous porous gold network with ligament and pore sizes tunable from ~5 to 100 nm. Unlike platinum black's fragile fractal structures, nanoporous gold forms a more mechanically robust interconnected framework. However, nanoporous gold has not seen widespread adoption in commercial BCIs, possibly due to concerns about long-term stability of the nanoporous structure under chronic electrochemical cycling.

Both approaches increase effective surface area while retaining the biocompatibility and electrochemical stability inherent to noble metals, but neither has achieved the commercial traction of SIROF or PEDOT:PSS. The durability concerns with platinum black, particularly its tendency to delaminate under mechanical stress, explain why companies like Blackrock and Precision Neuroscience have favored SIROF and PEDOT:PSS respectively: coatings that offer comparable impedance reduction with superior long-term mechanical stability. Neuralink has investigated surface treatments including iridium oxide to address impedance in their small-geometry electrodes, but specific coating choices for their commercial devices remain undisclosed.

For applications where platinum black remains attractive, such as in vitro microelectrode arrays or endovascular electrodes where insertion shear stress is minimized by catheter delivery, the sonicoplating technique or double-layer coating approaches offer viable paths to improved reliability. The endovascular neural interface insertion uses a catheter and vascular access sheath, eliminating shear stress that would otherwise damage platinum black coatings (Harris et al., 2025). In such applications, platinum black's electrochemical advantages can be realized without the mechanical limitations that preclude its use in penetrating cortical arrays.

Surface texturing

Micro- and nano-scale surface roughening increases effective surface area through purely geometric means. Plasma treatment of gold electrode sites increased average surface roughness from 1.7 to 22 nm and decreased electrode impedance by 98% (Chen et al., 2015). For conducting polymer films, surface roughness can be increased by over 90% through control of deposition parameters, with corresponding impedance decreases up to 88% (Oktay & Kaynak, 2015). Nanostructured electrodes with vertical nanowires show impedance values at least 9 times lower than flat reference electrodes, matching the increase in effective surface area measured by scanning electron microscopy (Wang et al., 2024).

Material comparison

The following table summarises impedance values at 1 kHz for different electrode materials (values from 12 μm diameter electrode sites unless otherwise noted):

| Material | Impedance at 1 kHz | Relative to Bare Pt | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bare platinum | 2,349 ± 531 kΩ | 1× | Lewis2024 |

| Bare gold | ~800–1,000 kΩ | ~0.4× | Multiple |

| Titanium nitride | Higher than IrOx | — | Weiland2002 |

| Nanoporous platinum | 97 ± 6.6 kΩ | 0.04× | Lewis2024 |

| Platinum black | ~100 kΩ | 0.04× | Seker2010 |

| SIROF (iridium oxide) | 70 ± 9.7 kΩ | 0.03× | Lewis2024 |

| SIROF (Utah array) | 6 kΩ | 0.003× | Negi2010 |

| PEDOT:PSS | 37 ± 2.6 kΩ | 0.016× | Lewis2024 |

| Nanoporous gold | ~30 kΩ | 0.013× | Seker2010 |

| IrOx/Pt gray composite | 2.45 kΩ·cm² | — | Wang2017 |

Note that impedance values are highly dependent on electrode size, deposition parameters, and measurement conditions. The table provides relative comparisons within similar experimental frameworks where available.

Amplifier Input Impedance

Reducing electrode impedance addresses thermal noise directly, but its benefits extend further through the recording chain. The electrode does not connect directly to a digitizer - it feeds into an amplifier's analog front-end, where impedance mismatch creates a voltage divider that attenuates neural signals before amplification can preserve them. The measured voltage relates to the true neural signal by:

where is the electrode impedance and is the amplifier input impedance. When electrode impedance approaches or exceeds amplifier input impedance, signal attenuation becomes substantial. A 100 kΩ electrode feeding a 10 MΩ amplifier loses approximately 1% of signal amplitude, which is negligible. But the same electrode feeding a 1 MΩ amplifier loses 9%, and if electrode impedance rises to 1 MΩ (common for small microelectrodes), attenuation reaches 50%. This frequency-dependent attenuation is particularly problematic for high-gamma signals, where electrode impedance is lower than at DC but amplifier input impedance may also decrease due to capacitive loading.

The voltage divider relationship also degrades common-mode rejection. Differential amplifiers reject interference signals that appear identically on both inputs, but this rejection depends on matched source impedances. When electrode impedances differ between recording and reference sites, which is inevitable given biological variability and electrode aging, common-mode signals convert to differential signals that the amplifier faithfully amplifies. A common-mode rejection ratio of 100 dB at the amplifier inputs can degrade to 60 dB or worse at the system level when electrode impedances are mismatched by even 10%.

Cascading Signal Losses: A Worked Example

To illustrate how these factors compound, consider a hypothetical epidural speech BCI attempting to decode inner speech from high-gamma activity:

Starting signal: 10 μV high-gamma power at the cortical surface (typical for attempted speech)

Step 1 - Inner speech attenuation: Inner speech produces ~52% of attempted speech amplitude

Step 2 - Dural attenuation: Assume 40% signal loss through the dura at high-gamma frequencies

Step 3 - Voltage divider loss: A 200 kΩ electrode feeding a 2 MΩ amplifier input

Final signal-to-noise ratio: With an amplifier noise floor of 2 μVrms

An SNR of 1.4 is marginal for reliable feature extraction. Now consider the same chain with optimized components—a low-impedance PEDOT:PSS-coated electrode (20 kΩ), a 100 MΩ input impedance amplifier, and <1 μVrms noise:

This three-fold improvement in SNR, achieved entirely through electrode coating and amplifier selection, could mean the difference between successful and failed speech decoding. The example illustrates why system-level optimization matters: no single component dominates, and marginal improvements at each stage compound multiplicatively.

Modern neural amplifiers address these constraints through careful front-end design. The canonical topology, established by Harrison and Charles in 2003, uses capacitive feedback around an operational transconductance amplifier with MOS-bipolar pseudoresistors to achieve input impedances exceeding 100 MΩ while maintaining sub-Hz low-frequency cutoffs. This architecture has become the foundation for most implantable neural recording ASICs, though implementations vary substantially in their noise-power tradeoffs.

The key specifications for neural amplifiers in speech BCI applications include input-referred noise, input impedance, bandwidth, and common-mode rejection ratio. Input-referred noise determines the minimum detectable signal. For high-gamma activity in the 1-10 μV range, amplifier noise below 2 μVrms is essential to maintain adequate signal-to-noise ratio. Input impedance must exceed electrode impedance by at least an order of magnitude to minimize voltage divider losses; for coated microelectrodes with impedances of 5-50 kΩ, input impedances above 1 MΩ suffice, but uncoated electrodes or small-diameter sites may require 100 MΩ or more. Bandwidth must extend beyond the high-gamma range of interest, at minimum to 300 Hz for speech envelope tracking, but preferably to 500 Hz or beyond to capture the full spectral content of speech-related neural activity. Common-mode rejection exceeding 80 dB is necessary to suppress power line interference and movement artifacts that would otherwise dominate the microvolt-scale signals of interest.

Commercial brain-computer interface systems have developed custom ASICs optimized for their specific electrode configurations and clinical constraints:

| System | Amplifier | Input-Referred Noise | Bandwidth | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blackrock (Utah Array) | Honey Badger ASIC | 0.35 μV resolution (15.5 ENOB) | DC to 7.5 kHz | Percutaneous; CerePlex headstages digitize at recording site |

| Neuralink (N1) | Custom 256-channel ASIC | 10 μV signals with 43-60 dB gain | 19.3 kHz sampling | Fully implantable; 5.2 μW per channel |

| Synchron (Stentrode) | Custom analog front-end | <2.5 μVrms | 1–300 Hz | Endovascular; CMRR >100 dB; BLE telemetry |

| Paradromics (Connexus) | Custom CMOS (180 nm) | 25–30 μV p-p noise floor | 32 kHz sampling | Optical data link; on-chip multiplexing |

| WIMAGINE (CEA) | Custom implantable ASIC | <1 μVrms | 0.5–300 Hz | Fully implantable; 13.56 MHz wireless power |

| Precision (Layer 7) | External commercial electronics | 2–5 μVrms typical | Configurable | Temporary implant; 1,024-channel array |

These specifications reveal a tradeoff between channel count, power consumption, and noise performance. Fully implantable systems like Neuralink and WIMAGINE must operate within strict thermal budgets - brain tissue tolerates temperature increases of only 1°C before risking damage - which constrains amplifier power and therefore noise performance. The Neuralink ASIC consumes approximately 6 mW total for 256 channels, achieving 5.2 μW per channel, but this power constraint limits the achievable noise floor. WIMAGINE achieves superior noise performance (<1 μVrms) but with only 64 channels and a bandwidth limited to 300 Hz. Systems with percutaneous connections or external electronics, like Blackrock's CerePlex headstages, can dedicate more power to achieving lower noise floors but sacrifice the clinical advantages of full implantation.

For epidural speech applications, the amplifier requirements are shaped by the signal characteristics discussed previously. High-gamma power in the 70-170 Hz band, attenuated by the dura and weakened by the inner speech amplitude reduction, may present at the electrode as signals of only a few microvolts. An amplifier with 2 μVrms input-referred noise would have a signal-to-noise ratio near unity for such signals - inadequate for reliable decoding. The WIMAGINE system's <1 μVrms noise specification, achieved with epidural placement in mind, represents the current benchmark for this application. Its 300 Hz bandwidth captures the high-gamma range relevant to speech, though extending to 500 Hz would provide margin for the upper harmonics of neural speech representations.

The voltage divider relationship creates a multiplicative penalty: every dB lost to impedance mismatch compounds the dB already lost to dural attenuation and inner speech amplitude reduction.

These factors combine multiplicatively. An electrode with high impedance feeding into an amplifier with marginal input impedance and high input-referred noise will have a noise floor that renders high-gamma recording impossible. Conversely, optimizing each component can extend the effective bandwidth well above 200 Hz.

Anatomical Challenges

The dura mater (Latin: "tough mother") is the outermost of the three meninges surrounding the brain. Composed primarily of dense collagenous connective tissue, it serves as the brain's primary mechanical protection. For epidural recording, the dura represents an unavoidable barrier between electrodes and neural tissue, and its electrical properties determine how much signal attenuation occurs.

Dura Thickness Over Speech Motor Areas

Dura thickness varies considerably across the cortical surface. A 2022 study examining 30 human cadavers measured regional variation (Protasoni et al., 2022):

- Frontal region: 0.38 ± 0.12 mm

- Temporal region: 0.35 ± 0.11 mm

- Parietal region: 0.44 ± 0.13 mm

- Occipital region: 0.46 ± 0.18 mm

For speech BCIs targeting Brodmann areas 6v (ventral premotor cortex) and 44 (pars opercularis/Broca's area), the relevant anatomy is the inferior frontal gyrus at the frontal-temporal junction. This suggests dura thickness of approximately 0.35-0.40 mm in speech motor regions; this is relatively thin compared to posterior regions.

Notably, dura over sulci is approximately 1.34× thicker than dura over gyri. Sex differences also exist, with frontal and temporal dura significantly thicker in males. These variations have implications for electrode placement and expected attenuation.

Important caveat: No studies have specifically measured dura thickness over areas 6v and 44 in living subjects. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography (OCT) measurements have found mean cranial dura depth of only 216 μm (0.216 mm), which is substantially thinner than cadaver studies suggest. In vivo measurements may differ from post-mortem values due to tissue changes after death.

How the Dura Attenuates Neural Signals

The dura acts as a volume conductor with resistive and capacitive properties. Neural currents must pass through this tissue layer before reaching epidural electrodes, and the electrical characteristics of the dura cause frequency-dependent signal attenuation.

High frequencies are attenuated more than low frequencies for two reasons. First, the capacitive component of tissue impedance decreases with frequency, creating a low-pass filtering effect. Second, higher frequency signals have shorter wavelengths, and the dura's thickness represents a larger fraction of the wavelength, increasing attenuation.

Torres Valderrama (2010) estimated approximately 80% signal attenuation by the dura for high-density grids with 4mm electrodes across 5-100 Hz (Torres Valderrama et al., 2010). However, they concluded this had "little effect on BCI performance for clinical grids". I will examine this finding more closely in the context of electrode size.

Epidural Macro-ECoG and Subdural Micro-ECoG Show Limited Signal Differences

The most direct evidence on dura attenuation comes from Bundy et al. (2014), who performed simultaneous epidural and subdural recordings in epilepsy surgery patients using both macro electrodes (2.3 mm diameter, 1 cm spacing) and micro electrodes (75 μm diameter, 1 mm spacing) (Bundy et al., 2014).

For micro electrodes, subdural signals were significantly higher than epidural at all frequencies below 150 Hz. Epidural micro-ECoG reached the noise floor at only 30 to 123 Hz, compared to 160 to 243 Hz for subdural placement, representing a deficit of at least 83 Hz in effective bandwidth.

For macro electrodes, the picture was markedly different. Statistical differences between epidural and subdural recordings were, in the authors' words, "small in amplitude and likely do not represent differences relevant to the ability of the signals to be used in a BCI system." The 1/f decrease in power was similar between placements. Epidural signals were slightly higher at 10 to 60 Hz, while subdural signals were slightly higher at 90 to 240 Hz, but neither difference appeared functionally significant.

This finding provides the primary empirical basis for optimism about epidural speech BCIs: larger electrodes appear relatively immune to dura attenuation while micro electrodes are severely affected.

Disambiguating the Confounded Variables

The Bundy experimental design confounds multiple variables. Electrode diameter, inter-electrode spacing, and geometric surface area all varied together between micro and macro conditions. The micro electrodes had 27 times smaller diameter, 10 times closer spacing, and roughly 700 times less surface area than the macro electrodes. Which factor drives susceptibility to dura attenuation cannot be determined from the empirical data alone.

Three candidate mechanisms warrant consideration:

- Geometric diameter and spatial averaging. Larger electrodes integrate signals over a wider cortical area, potentially capturing the superposition of many neural sources rather than depending on small, attenuated local fields. However, modeling by Viswam et al. (2019) suggests this effect diminishes rapidly with source distance. At z-distances exceeding 100 μm, electrodes ranging from 1×1 μm to 100×100 μm detect nearly identical signal amplitudes (Viswam et al., 2019). Since the dura is 350-400 μm thick over speech motor regions, spatial averaging differences between electrode sizes should be minimal for epidural recording.

- Inter-electrode spacing. Closer spacing might increase susceptibility to common-mode noise or reduce effective signal capture. However, Slutzky et al. (2010) used finite element modeling to specifically examine electrode spacing for epidural versus subdural placement and concluded that optimal spacing requirements were similar regardless of dural position (Slutzky et al., 2010). This suggests spacing is unlikely to be the primary driver of the micro-electrode signal deficit.

- Electrode impedance. This emerges as the most likely causal factor. Small electrodes have dramatically higher impedance due to reduced electrochemical surface area, causing higher thermal noise (which scales with √R per the Johnson-Nyquist relationship) and signal attenuation through voltage divider effects with amplifier input impedance. The Bundy micro-electrodes, with roughly 700 times less surface area than the macro-electrodes, would have correspondingly higher impedance.

Viswam et al. demonstrated that platinum-black coating, which increases electrochemical surface area without changing geometric dimensions, reduced signal attenuation from 68% to less than 2% for their smallest electrodes (Viswam et al., 2019). This result implies that impedance, not geometric diameter, is the limiting factor. The elevated noise floor of high-impedance micro-electrodes, combined with dura-attenuated high-gamma signals, causes the signal to fall below detection threshold at lower frequencies than would occur with low-impedance electrodes.

The definitive experiment, testing epidural recording with micro-scale electrodes surface-modified to achieve macro-electrode-like impedance, has not been performed. Until then, the relative contributions of these factors remain uncertain. However, the available evidence points toward electrochemical surface area (and thus impedance) as the dominant variable, with geometric diameter playing a secondary role primarily through its effect on impedance.

The authors supplemented their recordings with finite element modeling, simulating electrodes across a range of diameters in a spherical head model. The simulations predict that dura attenuation decreases monotonically with increasing electrode size. However, key methodological details are absent from the publication: the curve fitting procedure uses unspecified "high order sums of sine and Gaussian functions," no coefficients or functional forms are reported, and no code or simulation data are available. The modeling results are therefore directionally informative but not quantitatively replicable.

Chronic Implantation Comparisons

John et al. (2018) extended this comparison to include endovascular electrodes, comparing subdural, epidural, and endovascular arrays implanted chronically in sheep (John et al., 2018). Using electrodes ranging from 500 to 1000 μm in diameter, intermediate between the Bundy micro and macro scales, they found no significant effect of recording location on bandwidth (p = 0.75) or single trial signal-to-noise ratio. Decoding accuracy was comparable across all three modalities, with the authors concluding that "neither the dura nor the blood vessel significantly affect signal quality or performance."

Critically, this equivalence emerged only after chronic implantation of three to four weeks, when tissue responses had stabilized. The authors hypothesize that fibrous encapsulation around subdural electrodes may gradually increase their effective distance from cortical sources, eroding any initial proximity advantage. This temporal evolution suggests that acute comparisons may overestimate subdural superiority relative to what persists over clinically relevant timescales.

Spatial resolution showed more nuanced frequency dependence. At low frequencies between 8 and 24 Hz, subdural arrays achieved significantly better spatial resolution than epidural or endovascular placements. At frequencies above 24 Hz, including the high-gamma band critical for speech decoding, no significant differences emerged between recording locations. This frequency-dependent pattern aligns with theoretical predictions: higher frequency signals, arising from more spatially localized neural populations, may be equally attenuated regardless of the intervening tissue once electrode size exceeds certain thresholds.

Tissue Response Over Time

Acute recording performance is necessary but not sufficient for clinical BCIs. Devices must maintain signal quality over months to years of implantation. The body's response to chronic foreign body presence, particularly fibrosis at the electrode-tissue interface, represents a major challenge for long-term neural recording.

The Foreign Body Response

When any material is implanted in the body, a stereotyped inflammatory cascade begins. For epidural electrodes, this process involves:

-

Acute phase (hours to days): Surgical trauma activates microglia and triggers acute inflammatory response

-

Subacute phase (days to weeks): Astrocytes activate for wound healing; inflammatory macrophages accumulate

-

Chronic phase (weeks to months): Meningeal fibroblasts proliferate, creating fibrous connective tissue

-

Encapsulation (months onward): Electrode becomes encased in fibrous tissue; impedance stabilizes

Tissue encapsulation is the final stage of anti-inflammatory wound healing and persists throughout the lifetime of the implant (Yan et al., 2023). Progressive fibrous overgrowth can completely encapsulate electrodes as early as one month after implantation (Schendel et al., 2014).

Quantitative Evidence Across Species

Multiple studies have characterized the chronic tissue response to epidural and subdural ECoG implants:

Sheep (WIMAGINE, 10 months)

Significant thickening of the dura mater was observed below the implant, likely due to dural injury during craniotomy and subsequent meningeal fibroblast activation (Sauter-Starace et al., 2019). Fibrotic scar tissue was confirmed by microscopic investigation, and calcifications extended from craniotomy edges toward the center. Despite this tissue response, effective bandwidth remained stable at approximately 230 Hz throughout the implantation period, well above the 170 Hz upper limit of the high-gamma band.

Dogs (6 months subdural)

Quantitative histology in six beagles with subdural electrode arrays revealed dorsal encapsulation (between dura and array) of 1,179 ± 527 μm, significantly thicker than ventral encapsulation (between array and arachnoid) of 173 ± 109 μm and contralateral control dura of 150 ± 49 μm (Yan et al., 2020). Thick fibrous proliferation was observed in the epidural space and subcutaneous regions. Mild angiogenesis and fibrosis occurred in all animals, with inflammatory cell infiltration in most animals, but no severe infections or complications.

Non-human primates (15 months subdural)

Two cynomolgus monkeys implanted with wireless 32-channel subdural arrays showed thickening of reactive tissue around the electrode array after 15 months (Yan et al., 2023). Histological examination revealed no evident inflammation in the cortex despite the tissue proliferation. Gain factor analysis demonstrated that tissue proliferation under electrodes reduced signal amplitude power, though time-frequency analyses showed similar signal features between acute and chronic phases.

Humans (WIMAGINE, 32 months epidural)

Two tetraplegic patients bilaterally implanted with WIMAGINE showed "limited decrease of signal average level (RMS), spectral distribution, and SNR, and remarkable steadiness of effective bandwidth" over 32-month and 14-month follow-up periods respectively (Larzabal et al., 2021). No direct histological data are available from human subjects, but functional recordings were maintained throughout, with time-frequency maps during motor imagery showing high discrimination both one month after surgery and after two years.

Impact of Foreign Body Response on Signal Quality

The critical question is whether tissue proliferation degrades signals enough to impair BCI function. The evidence suggests a nuanced answer:

Signal amplitude decreases

Analysis of gain factors in NHP studies found that "tissue proliferation under electrodes reduced the amplitude power of signals" (Yan et al., 2023). Power spectral density and RMS values showed gradual decreases across all frequencies, stabilizing after approximately 300 days.

Effective bandwidth is preserved

Despite tissue thickening, the frequency range over which neural signals exceed the noise floor remained remarkably stable. WIMAGINE sheep data showed effective bandwidth of approximately 230 Hz maintained throughout the 10-month implantation period (Sauter-Starace et al., 2019). Human WIMAGINE recordings similarly demonstrated remarkable steadiness of effective bandwidth over 32 months (Larzabal et al., 2021).

Functional decoding remains viable

Motor decoding accuracy was maintained in chronic WIMAGINE deployments, with time-frequency discrimination during motor imagery preserved from one month to two years post-implantation (Larzabal et al., 2021). Chronic ECoG recordings from NeuroPace RNS systems in epilepsy patients have demonstrated signal stability over periods exceeding seven years, suggesting that ECoG-based BCIs can maintain functional performance despite tissue encapsulation (Nurse et al., 2018).

Impedance stabilization occurs within approximately 18 weeks, with tissue proliferation correlating to impedance rise as early as one week (Henle et al., 2011). After stabilization, chronic recordings appear sustainable, but the reduced signal amplitude places greater demands on amplifier noise performance to maintain adequate SNR.

What Speech Decoding Actually Requires

Not all neural frequencies contribute equally to speech decoding. Understanding which signals matter reveals the specific challenges epidural placement must overcome.

The Speech Production Network

Speech arises from a distributed cortical network, classically described as linking posterior comprehension areas to anterior motor regions. In the Wernicke-Geschwind model, auditory speech is processed in the superior temporal gyrus, specifically the posterior portion known as Wernicke's area (Brodmann area 22), then transmitted via the arcuate fasciculus to Broca's area in the inferior frontal gyrus (BA 44/45), which orchestrates motor planning for articulation. The arcuate fasciculus, a white matter tract arching around the Sylvian fissure, provides the primary dorsal pathway connecting these regions; lesions along this tract produce conduction aphasia, characterized by intact comprehension and fluent speech but impaired repetition (Geschwind, 1970).

However, the classical model describes language comprehension and high-level planning, not the motor execution that speech BCIs must decode. For direct articulator control, the critical structure is the ventral sensorimotor cortex (vSMC), located in the ventral precentral and postcentral gyri along the Sylvian fissure. Chang and colleagues demonstrated that vSMC contains somatotopically organized representations of speech articulators - lips, jaw, tongue, and larynx - arranged dorsoventrally in a pattern that recapitulates the rostral-to-caudal layout of the vocal tract (Bouchard et al., 2013). These representations overlap at the single-electrode level and coordinate temporally during syllable production, generating population-level patterns organized by phonetic features rather than discrete phoneme identities.

The middle precentral gyrus (midPrCG), situated between dorsal hand representations and ventral orofacial cortex, has emerged as another critical region. Neurosurgical dissection studies show that midPrCG exhibits unique sensorimotor and multisensory functions relevant to speech processing, distinct from both the motor execution role of vSMC and the classical planning role attributed to Broca's area (Silva et al., 2022). Recent evidence suggests that Broca's area itself contains minimal information about orofacial movements or phonemes during production, challenging its traditional role in motor planning (Willett et al., 2023).

The superior temporal gyrus (STG) processes incoming speech sounds - populations of neurons respond to acoustic-phonetic features in vowels and consonants, with the posterior STG recognizing phoneme categories even across variations in speaker and accent (Chang et al., 2010). STG activity reflects perception rather than production intent, though auditory feedback loops connect it to motor regions during speech.

BCI Electrode Targets

Current high-performance speech BCIs target motor and premotor regions rather than classical language areas:

ECoG systems (Moses 2021, Metzger 2023) place subdural electrode arrays over the ventral sensorimotor cortex, covering regions where high-gamma activity (70–150 Hz) tracks articulator kinematics with approximately 50 ms temporal resolution. The 253-electrode array in Metzger et al. spanned vSMC and surrounding cortex, achieving 78 words per minute with 25% median word error rate.

Intracortical arrays (Willett 2023, Kunz 2025) implant microelectrode arrays in HCP-identified area 6v (orofacial motor cortex) of ventral precentral gyrus and area 44 of inferior frontal gyrus. Willett et al. found that speech articulators are highly intermixed at the single-neuron level within 3.2 × 3.2 mm² arrays, with robust tuning to jaw, larynx, lips, and tongue movements all represented within the same array. This placement achieved 62 words per minute with 9.1% word error rate on a 50-word vocabulary.

The superior temporal gyrus shows speech-related activity during perception but is not a primary target for production-focused BCIs - its signals reflect acoustic processing of heard speech rather than motor intentions.

Frequency Bands and Decoding Features

Not all neural frequencies contribute equally to speech decoding. Understanding which signals carry articulatory information, and which merely reflect preparatory or modulatory activity, is essential for BCI design.

Beta (13–30 Hz): Shows characteristic desynchronization several hundred milliseconds before movement onset, reflecting release of motor inhibition (Pfurtscheller & Silva, 1999). Beta suppression indicates speech intention but does not encode specific phonemes or articulator positions.

High-gamma (70–150 Hz): The primary feature for speech decoding. High-gamma power correlates tightly with local neuronal spiking activity across stimulus manipulations, whereas low-gamma (30–80 Hz) shows much weaker correlation and can become anti-correlated with firing rates under certain conditions (Ray & Maunsell, 2011). This tight coupling makes high-gamma a reliable proxy for the population spiking that drives articulator movements. Early ECoG studies established high-gamma as the dominant signal for cortical speech mapping (Crone et al., 2006).

High-gamma offers two properties essential for speech decoding:

- Temporal precision: Approximately 50 ms resolution matches the rapid dynamics of phoneme production

- Spatial specificity: Distinct electrode sites show selectivity for specific articulators and phonetic features, enabling discrimination of labial versus coronal versus dorsal consonants (Bouchard et al., 2013)

Moses et al. extracted 70–150 Hz high-gamma power to achieve 93% peak accuracy (75% median) on a 50-word vocabulary. Metzger et al. used broadband high-gamma extraction for their 78 WPM system. Willett et al., using intracortical arrays that directly record spiking activity, found a log-linear relationship between electrode count and error rate: doubling the electrode count cuts word error rate by approximately half (factor of 0.57).

Signal Amplitudes and SNR Considerations

Calibration data from micro-ECoG studies provide baseline amplitude references. Kaiju et al. reported resting ECoG voltage RMS of 18 ± 6.0 μV, with evoked responses reaching several hundred microvolts during somatosensory stimulation (Kaiju et al., 2017). This suggests working SNR in the 10–20 dB range for subdural recordings over active cortex.

The literature does not specify explicit SNR thresholds for speech decoding, performance is typically reported in terms of accuracy, word error rate, and communication speed rather than input signal quality metrics. The available benchmarks suggest that current subdural and intracortical systems achieve sufficient SNR for practical decoding when electrodes are placed directly over or within vSMC.

Inner Speech and Signal Magnitude

Inner speech, imagined speaking without motor output, engages a similar but attenuated cortical network. Kunz et al. found that inner speech produces approximately 52% of the neural amplitude observed during attempted speech in the same recording locations, yet achieved 74% accuracy decoding imagined sentences from a 125,000-word vocabulary using intracortical arrays in area 6v and area 44 (Kunz et al., 2025). The highly correlated but weaker magnitude of inner speech signals sets a higher bar for recording quality: any attenuation from electrode placement further narrows the available margin for reliable decoding.

References

- Kunz, E., et al. (2025). Decoding inner speech for brain-computer interfaces. Cell, 188(5), 1182-1195. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2025.01.012

- Cogan, S., Plante, T., & Ehrlich, J. (2022). Sputtered iridium oxide films for neural stimulation electrodes. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials, 110(5), 1045-1052. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.34979

- Saurav, K., Bhowmick, S., Bhatt, P., Saxena, K., & Mukherjee, B. (2025). PEDOT:PSS based conducting polymer electrodes for biomedical sensing applications. Nature Microsystems and Nanoengineering, 11, 52. doi:10.1038/s41378-025-00876-3

- Bianchi, M., et al. (2022). PEDOT:PSS coatings for flexible neural microelectrodes: characterization and comparison. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 135, 112667. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2022.112667

- Lewis, C., Bhaskaran, N., Bhatt, P., Saxena, K., & Lee, C. (2024). Comparison of electrode materials for chronic neural recording. Journal of Neural Engineering, 21(1), 016009. doi:10.1088/1741-2552/ad1d7a

- Cuttaz, E., Chapman, C., Goding, J., Vallejo-Giraldo, C., & Green, R. (2022). PEDOT:PSS composite electrodes for chronic neural interfaces. Science Advances, 8(32), eabq7001. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abq7001

- Boehler, C., Carli, S., Briand, D., Stieglitz, T., & Asplund, M. (2020). Tutorial: guidelines for standardized performance tests for electrodes intended for neural interfaces and bioelectronics. Nature Protocols, 15, 3557-3578. doi:10.1038/s41596-020-0389-2

- Oldroyd, P., & Malliaras, G. (2023). PEDOT:PSS neural interface devices: progress and prospects. Advanced Materials Technologies, 8(5), 2200934. doi:10.1002/admt.202200934

- Cogan, S. (2008). Neural stimulation and recording electrodes. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 10, 275-309. doi:10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160518

- Negi, S., Bhandari, R., Rieth, L., Van Wagenen, R., & Solzbacher, F. (2010). Neural electrode degradation from continuous electrical stimulation: comparison of sputtered and activated iridium oxide. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 186(1), 8-17. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.10.016

- Qiang, Y., Artoni, P., Seo, K., Culaclii, S., Vu, V., & Fang, H. (2025). Platinum black electrodeposition for neural interfaces. Scientific Reports, 15, 1876. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-85698-7

- Kim, R., & Nam, Y. (2013). Novel platinum black electroplating technique improving mechanical stability. Proceedings of the 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 184-187. doi:10.1109/EMBC.2013.6609468

- Harris, A., et al. (2025). Endovascular neural stimulation with platinum and platinum black modified electrodes. Scientific Reports, 15, 9394. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-93941-2

- Ferguson, J., Boldt, C., & Redish, A. (2010). Improving impedance of implantable microwire multi-electrode arrays by ultrasonic electroplating of durable platinum black. Frontiers in Neuroengineering, 3, 5. doi:10.3389/fneng.2010.00005

- Yin, P., Liu, Y., Xiao, L., & Zhang, C. (2021). Advanced metallic and polymeric coatings for neural interfacing: structures, properties and tissue responses. Polymers, 13(16), 2834. doi:10.3390/polym13162834

- Wang, L., et al. (2019). The use of a double-layer platinum black-conducting polymer coating for improvement of neural recording and mitigation of photoelectric artifact. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 145, 111661. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2019.111661

- Seker, E., Reed, M., & Begley, M. (2009). Nanoporous gold: fabrication, characterization, and applications. Materials, 2(4), 2188-2215. doi:10.3390/ma2042188

- Chen, Y., Kim, Y., Bhatt, P., Bhowmick, S., & Bhatt, M. (2015). Plasma treatment of gold electrode surfaces for improved neural recording. Journal of Neural Engineering, 12(5), 056009. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/12/5/056009

- Oktay, B., & Kaynak, E. (2015). Surface roughness of PEDOT:PSS films and its effect on electrode impedance. Synthetic Metals, 209, 559-566. doi:10.1016/j.synthmet.2015.08.036

- Wang, Y., Seo, J., Lee, S., Chang, E., & Hong, G. (2024). Nanowire electrodes for neural recording with reduced impedance. Scientific Reports, 14, 23418. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-73292-z

- Protasoni, M., et al. (2022). The human dura mater: ultrastructural features and regional thickness variations. Clinical Anatomy, 35(7), 912-920. doi:10.1002/ca.23932

- Torres Valderrama, A., Oostenveld, R., Vansteensel, M., Huiskamp, G., & Ramsey, N. (2010). Gain of the human dura in vivo and its effects on invasive brain signal feature detection. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 187(2), 270-279. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.01.019

- Bundy, D., et al. (2014). Characterization of the effects of the human dura on macro- and micro-electrocorticographic recordings. Journal of Neural Engineering, 11(1), 016006. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/11/1/016006

- Viswam, V., Obien, M., Franke, F., Frey, U., & Hierlemann, A. (2019). Optimal electrode size for multi-scale extracellular-potential recording from neuronal assemblies. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 385. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00385

- Slutzky, M., Jordan, L., Krieg, T., Chen, M., Mogul, D., & Miller, L. (2010). Optimal spacing of surface electrode arrays for brain-machine interface applications. Journal of Neural Engineering, 7(2), 026004. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/7/2/026004

- John, S., et al. (2018). Signal quality of simultaneously recorded endovascular, subdural and epidural signals are comparable. Scientific Reports, 8, 8427. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-26457-7

- Yan, D., et al. (2023). Chronic subdural electrocorticography in nonhuman primates by an implantable wireless device for brain-machine interfaces. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 1029385. doi:10.3389/fnins.2023.1029385

- Schendel, A., et al. (2014). The effect of micro-ECoG substrate footprint on the meningeal tissue response. Journal of Neural Engineering, 11(4), 046011. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/11/4/046011

- Sauter-Starace, F., et al. (2019). Long-term sheep implantation of WIMAGINE, a wireless 64-channel electrocorticogram recorder. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 847. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00847

- Yan, J., et al. (2020). Histopathological and electrophysiological evaluation of chronic subdural electrodes in dogs. Journal of Neural Engineering, 17(3), 036013. doi:10.1088/1741-2552/ab91e3

- Larzabal, C., et al. (2021). Long-term epidural electrocorticography for brain-machine interface in a tetraplegic patient. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15, 789906. doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.789906

- Nurse, E., et al. (2018). Consistency of long-term subdural electrocorticography in humans. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 65(2), 344-352. doi:10.1109/TBME.2017.2768442

- Henle, C., Raab, M., Cordeiro, J., Doostkam, S., Schulze-Bonhage, A., Stieglitz, T., & Rickert, J. (2011). First long term in vivo study on subdurally implanted micro-ECoG electrodes, manufactured with a novel laser technology. Biomedical Microdevices, 13(1), 59-68. doi:10.1007/s10544-010-9471-9

- Geschwind, N. (1970). The organization of language and the brain. Science, 170(3961), 940-944. doi:10.1126/science.170.3961.940

- Bouchard, K., Mesgarani, N., Johnson, K., & Chang, E. (2013). Functional organization of human sensorimotor cortex for speech articulation. Nature, 495(7441), 327-332. doi:10.1038/nature11911

- Silva, A., Metzger, S., Moses, D., & Chang, E. (2022). The neurosurgical atlas of speech and language cortex. Journal of Neurosurgery, 136(5), 1377-1391. doi:10.3171/2021.4.JNS21616

- Willett, F., et al. (2023). A high-performance speech neuroprosthesis. Nature, 620, 1031-1036. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06377-x

- Chang, E., Rieger, J., Johnson, K., Berger, M., Barbaro, N., & Knight, R. (2010). Categorical speech representation in human superior temporal gyrus. Nature Neuroscience, 13(11), 1428-1432. doi:10.1038/nn.2641

- Pfurtscheller, G., & Silva, F. (1999). Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: basic principles. Clinical Neurophysiology, 110(11), 1842-1857. doi:10.1016/S1388-2457(99)00141-8

- Ray, S., & Maunsell, J. (2011). Different origins of gamma rhythm and high-gamma activity in macaque visual cortex. PLOS Biology, 9(4), e1000610. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000610

- Crone, N., Sinai, A., & Korzeniewska, A. (2006). High-frequency gamma oscillations and human brain mapping with electrocorticography. Progress in Brain Research, 159, 275-295. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(06)59019-3

- Kaiju, T., et al. (2017). High spatiotemporal resolution ECoG recording of somatosensory evoked potentials with flexible micro-electrode arrays. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 11, 20. doi:10.3389/fncir.2017.00020