Electrode Placement Strategies for Speech BCIs

For 160 years, neuroscientists assumed that Broca's area, the "speech center" in the left inferior frontal gyrus, was where speech BCIs should record. They were wrong. Systematic testing across electrode types and brain regions has revealed that the ventral precentral gyrus, not Broca's area, yields the signals that enable accurate speech decoding. This finding, now replicated across labs using both surface and penetrating electrodes, has reoriented the field and affirmed the principle that choice of electrode placement matters more than the choice of electrode technology.

Electrode Types

Four approaches to neural interfacing have emerged, each trading off invasiveness against signal resolution. They progress from least to most direct brain contact: epidural (outside the dura), endovascular (through blood vessels), subdural (on the brain surface), and intracortical (penetrating cortical tissue). Before comparing brain regions, I will briefly describe each of these approaches.

Epidural

Epidural electrodes sit outside the dura mater, the tough membrane surrounding the brain, to record data without entering the intracranial space. This offers distinct advantages over subdural implantation as electrodes remain outside the cerebrospinal fluid space, reducing invasiveness and the potential impact of a surgical site infection (Bundy et al., 2014). Because the electrodes never contact brain tissue, the implant can be removed without causing neural damage, a reversibility that subdural and intracortical approaches cannot match.

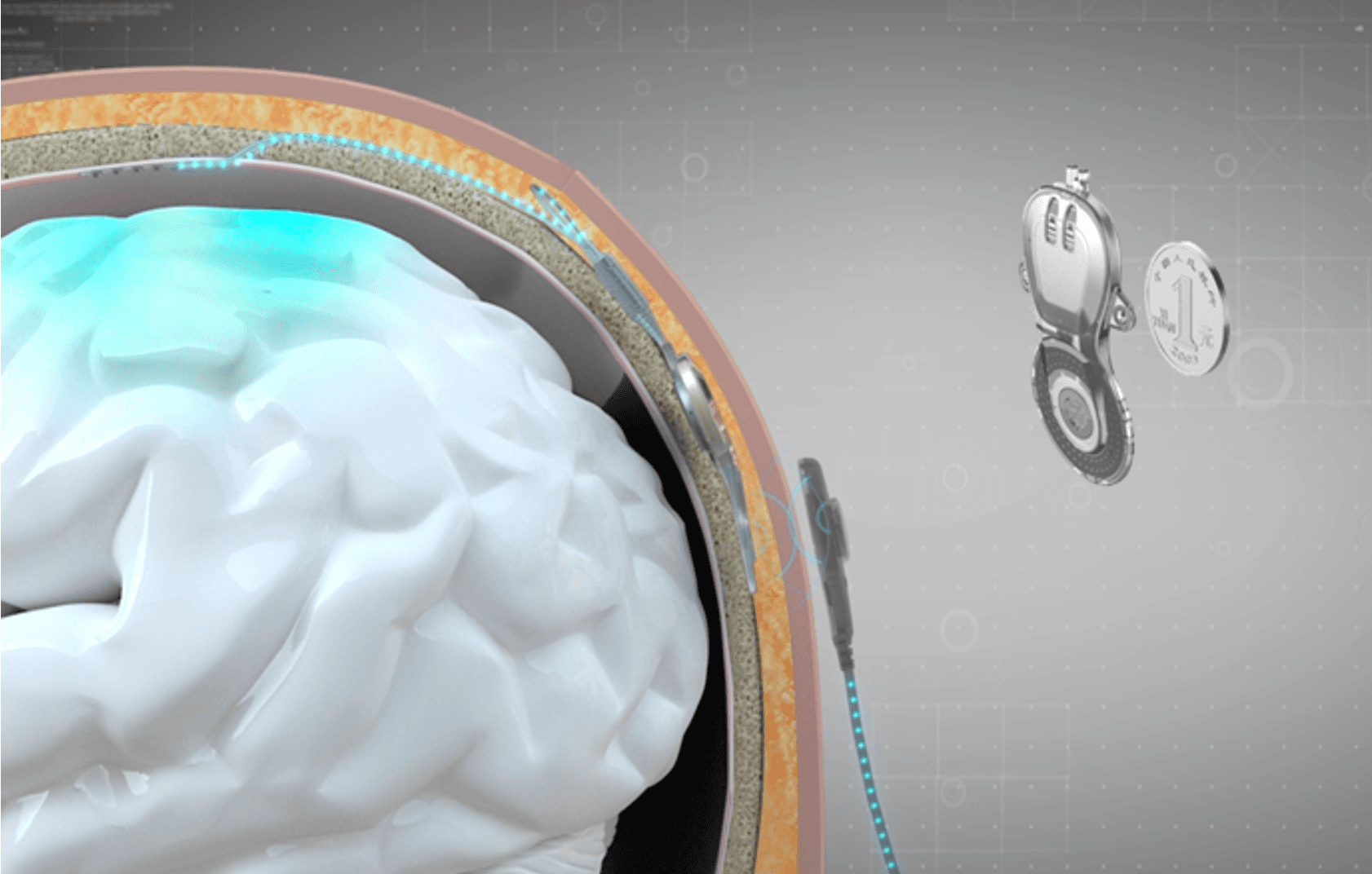

The NEO system developed by Tsinghua University exemplifies this approach using a 25mm-diameter coin-sized titanium alloy implant that fits within the skull itself, with electrodes covering the outer layer of the dura mater. The system uses eight epidural electrodes with 3.2mm diameter contacts and 8mm center-to-center spacing, recording local field potentials at 1kHz sampling rate (Liu et al., 2024).

The NEO implant requires no battery. Power is supplied remotely through near-field induction from an external coil attached to the scalp, while neural signals transmit wirelessly via Bluetooth. In a patient with complete C4 spinal cord injury, the system achieved a grasping detection F1-score of 0.91 and 100% success rate in object transfer tests over nine months of home use (Liu et al., 2024). Neural recordings remained stable for over 18 months, and the decoder maintained performance for over 6 months without recalibration (Yao et al., 2025).

A common assumption is that epidural placement fundamentally compromises signal quality, but the evidence is more nuanced. For macro-scale electrodes (2mm diameter, 1cm spacing), while there are statistical differences between epidural and subdural recordings, these differences are small in amplitude and likely do not represent differences relevant to the ability of the signals to be used in a BCI system (Bundy et al., 2014). NEO's electrodes fall into this macro-scale category, meaning signal attenuation through the dura is not the limiting factor.

The picture changes for micro-scale electrodes. Subdural contacts have significantly higher spectral amplitudes and reach the noise floor at a higher frequency than epidural contacts (Bundy et al., 2014). This means that as electrode technology pushes toward higher-density arrays, the direction Precision Neuroscience and others are pursuing, epidural placement becomes increasingly disadvantageous.

For speech specifically, NEO's constraint is spatial coverage rather than signal quality. Eight macro-electrodes provide sufficient resolution for detecting grasp intentions, but speech decoding requires capturing the simultaneous activity of dozens of articulatory representations distributed across ventral sensorimotor cortex. The successful speech BCIs use either hundreds of surface electrodes (UCSF's 253-electrode ECoG arrays) or intracortical access to single neurons, demanding subdural placement or cortical penetration.

Endovascular

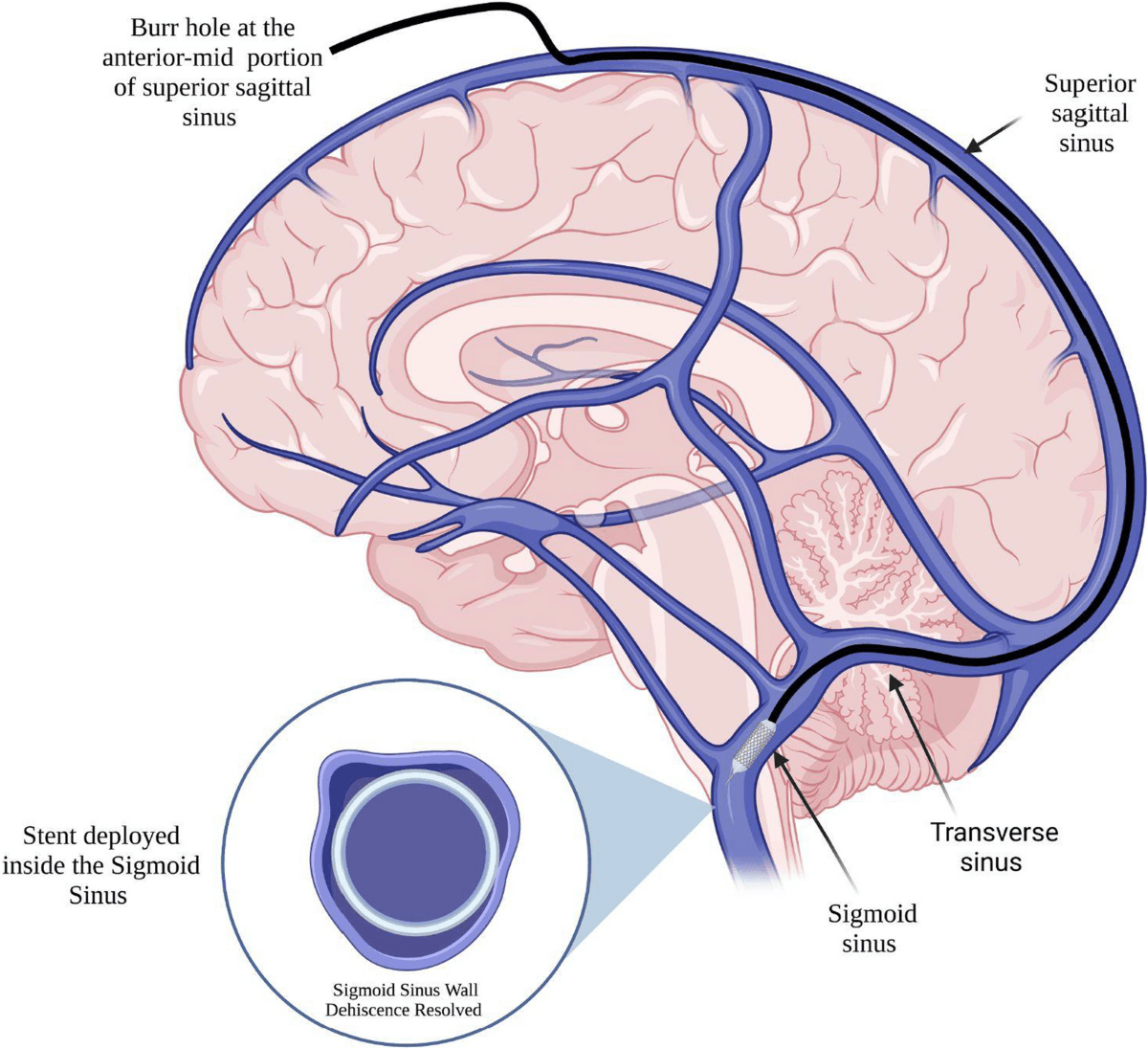

Synchron's Stentrode takes a radically different approach. Rather than opening the skull, the device is delivered through the jugular vein using standard neurointerventional techniques, then positioned within the superior sagittal sinus, the large blood vessel running along the brain's midline above motor cortex (Mitchell et al., 2023). The procedure uses techniques familiar to any neurointerventionalist who treats stroke, eliminating the need for craniotomy entirely.

The sensing device contains 16 platinum electrodes with 0.3mm² surface area and 3mm intercontact spacing, connected via a transvascular lead to an implantable receiver-transmitter unit in a subclavicular pocket (Mitchell et al., 2023). Like a pacemaker, the entire system sits beneath the skin with no external hardware.

The COMMAND early feasibility study demonstrated that in 100% of patients, the Stentrode was accurately deployed with a median deployment time of 20 minutes, achieving target motor cortex coverage. No neurologic safety events were reported during the 12-month study period (Levy et al., 2024). The COMMAND study is the first FDA-approved investigational device exemption trial of a permanently implanted BCI (Levy et al., 2024). Ten patients have received the device across clinical trials in the US and Australia.

After implantation in the SWITCH clinical trial, patients were able to use the Stentrode system unsupervised in their homes to send text messages, conduct online shopping, and manage their finances (Mitchell et al., 2023). The system pairs with eye-tracking for cursor movement, using decoded motor intent as a "brain click" to select targets - simple, thought-derived expressions of intent, converted into digital actions on computers like scrolls, clicks and double-clicks (Levy et al., 2024).

This approach enables text-based communication but not speech decoding. Synchron users can type messages that are then vocalized through text-to-speech software, but the system does not decode the neural patterns underlying attempted speech. Current limitations in channel density and spatial resolution constrain the complexity of decoded outputs, and with 16 electrodes sampling from a single vessel over dorsal motor cortex, the Stentrode lacks both the electrode count and the anatomical positioning over ventral precentral gyrus, area 6v, that speech decoding requires. Synchron's roadmap focuses on motor control applications: cursor control, device operation, and restoring digital independence for people with paralysis.

Subdural

Subdural electrocorticography (ECoG) places flexible electrode grids directly on the brain surface without penetrating tissue. The UCSF/Chang Lab pioneered high-density configurations using 253-electrode arrays covering speech sensorimotor cortex, while Johns Hopkins deploys 128-electrode grids over motor, premotor, and somatosensory areas (Moses et al., 2021) (Metzger et al., 2023). Individual electrodes measure 2mm diameter with 4mm center-to-center spacing. These systems record local field potentials, particularly high-gamma activity (70-170 Hz), which captures population-level neural dynamics rather than individual neurons.

ECoG studies consistently target the ventral sensorimotor cortex spanning the central sulcus, including both motor (precentral gyrus) and somatosensory (postcentral gyrus) regions. The Chang Lab's detailed cortical mapping identified speech-active areas through direct electrical stimulation during neurosurgery, allowing precise grid placement (Chartier et al., 2018). The superior temporal gyrus also shows speech-relevant activity but primarily for auditory/perceptual aspects rather than production.

The Metzger et al. 2023 Nature paper achieved 78 words per minute with 25% median WER using 253 ECoG electrodes, with training completed in under 2 weeks (Metzger et al., 2023). The 2025 Littlejohn et al. paper solved the critical latency problem, achieving sub-1-second real-time streaming synthesis compared to previous 8-second delays - representing the fastest brain-to-voice system demonstrated (Littlejohn et al., 2025). Johns Hopkins work showed remarkable 3-month stability with 90.6% accuracy for command decoding without any recalibration, demonstrating "plug-and-play" potential for home use (Luo et al., 2023).

Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays

Intracortical microelectrode arrays represent the most invasive but highest-resolution approach to neural recording. By penetrating directly into cortical tissue, these devices access what surface electrodes cannot: the electrical activity of individual neurons. This single-unit resolution has enabled the most impressive speech decoding results to date.

The Utah Array

The dominant platform for intracortical speech research remains the "Utah array", a 96-electrode silicon microelectrode array manufactured by Blackrock Neurotech, arranged on a 4×4 mm platform with electrodes extending approximately 1.5 mm into the cortex. First used in humans in 2004 as part of the BrainGate clinical trial (NCT00912041), these arrays have accumulated over two decades of human implant experience.

The BrainGate2 consortium, spanning Stanford, Brown, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Providence VA, has systematically validated this approach. A comprehensive evaluation of 20 years of data from 14 trial participants, published in 2025, found that arrays successfully recorded neural spiking waveforms on an average of 35.6% of electrodes, with only a 7% decline over enrollment periods extending up to 7.6 years (Hahn et al., 2025). This stability, while modest compared to epidural recordings, has proven sufficient for high-performance decoding.

Record-Breaking Speech Decoding

The Stanford Neural Prosthetics Translational Laboratory, led by Jaimie Henderson and the late Krishna Shenoy, has achieved the most impressive speech decoding results in the field. In 2023, Willett and colleagues demonstrated a speech-to-text BCI that decoded attempted speech at 62 words per minute. That's 3.4 times faster than the previous record for any BCI type and approaching the 160 words per minute of natural conversation (Willett et al., 2023).

The study participant, an individual with ALS who could no longer speak intelligibly, achieved a 9.1% word error rate on a 50-word vocabulary (2.7 times fewer errors than the previous state-of-the-art) and 23.8% word error rate on a 125,000-word vocabulary. This was the first successful demonstration of large-vocabulary decoding. Critically, four microelectrode arrays were placed in two locations: two in area 6v (ventral premotor cortex) and two in area 44 (part of Broca's area). The area 6v arrays proved more informative, reinforcing findings from ECoG studies about the primacy of ventral motor cortex for speech.

In 2025, the same group demonstrated "plug-and-play" stability. A participant with ALS achieved 97.5% accuracy on a 50-word vocabulary on the first day of BCI use, just 25 days post-surgery, without any prior decoder training specific to that individual (Fan et al., 2025). This transfer learning approach used neural network decoders pre-trained on data from other participants, suggesting that speech representations may be sufficiently consistent across individuals to enable rapid deployment.

Why Intracortical Works for Speech

Intracortical recordings reveal organizational principles invisible to surface electrodes. The Willett 2023 study found that tuning to different speech articulators (lips, tongue, jaw, larynx) is spatially intermixed rather than segregated, meaning that even a small patch of cortex contains information about multiple articulators. This redundancy explains how accurate decoding remains possible despite recording from a limited region and even after electrode degradation.

The study also demonstrated that detailed articulatory representations of phonemes persist years after paralysis, despite the participant having not spoken normally for years. This finding, consistent across multiple participants in the BrainGate trial, suggests that motor speech areas maintain their computational organization even without use, a critical enabling factor for speech restoration in people with longstanding paralysis.

Emerging Intracortical Platforms

The Utah array's limitations, including rigid silicon construction, moderate electrode density, and percutaneous connectors requiring daily maintenance, have spurred development of next-generation platforms.

Neuralink has advanced rapidly into clinical trials with its N1 implant, featuring 1,024 electrodes distributed across 64 flexible polymer threads, each thinner than a human hair. A proprietary surgical robot (R1) inserts threads at approximately 200 μm depth increments, a precision impossible with manual techniques. The first human implant occurred in January 2024 at Barrow Neurological Institute; as of mid-2025, nine participants have received N1 implants across trials in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The company received FDA Breakthrough Device designation for a speech restoration module in April 2025, with a dedicated speech trial enrolling 10-15 participants with ALS and other conditions beginning October 2025.

Paradromics, an Austin-based competitor, received FDA approval in late 2024 for the first long-term clinical trial formally targeting synthetic voice generation. Their platform features a roughly 7.5 mm diameter array of platinum-iridium electrodes penetrating approximately 1.5 mm into cortex, similar depth to Utah arrays but with more than four times the electrode count. The trial will implant devices in the ventral motor cortex region controlling lips, tongue, and larynx, with the explicit goal of converting neural patterns into real-time speech audio using recordings of participants' pre-injury voices. "Arguably, the greatest quality of life change you can deliver right now with BCI is communication," said CEO Matt Angle.

The Invasiveness Tradeoff

Intracortical arrays face fundamental biological challenges. Foreign body responses such as glial scarring, chronic inflammation, and neuronal die-back around electrodes, can degrade signal quality over time. The BrainGate long-term data suggests this degradation is gradual rather than catastrophic, but it remains a concern for lifetime devices.

Surgical implantation requires craniotomy which carries inherent risks. In the BrainGate safety analysis of 14 participants over 12,203 device-days, there were 68 device-related adverse events including 6 serious adverse events, though notably no intracranial infections, no deaths related to the device, and no events requiring device explantation (Simeral et al., 2024).

For speech applications specifically, intracortical approaches face a spatial challenge. The articulatory motor cortex (area 6v) and associated speech regions span a broader area than can be covered by a single 4×4 mm array. Current solutions involve placing multiple arrays, but future platforms may require larger coverage areas or more distributed electrode placement strategies to capture the full neural dynamics of speech production.

Which Brain Regions Support Speech BCI?

Of the four approaches to neural interfacing, subdural ECoG and intracortical arrays have emerged as the serious contenders for speech restoration. Epidural recording lacks the resolution to capture speech-related activity, and endovascular approaches, while promising for gross motor commands, haven't demonstrated the fine-grained signals needed for decoding attempted articulation. But the more surprising finding isn't which technology works - it's which brain regions work. After 160 years of assuming that Broca's area held the key to speech production, systematic testing has revealed a different winner.

The Classical Model and Its Problems

For over a century, neuroscience textbooks presented a tidy story. Broca's area (Brodmann areas 44 and 45 in the left inferior frontal gyrus) programs speech, then sends commands to motor cortex for execution. Pierre Paul Broca established this model in the 1860s based on two patients with severe speech deficits and frontal lesions. The story proved durable partly because it fit intuitive expectations of a "language center" near the motor strip controlling speech muscles.

But the story had cracks. When researchers began examining Broca's original cases with modern MRI, they discovered that both patients (Leborgne and Lelong) had damage extending well beyond area 44/45 into underlying white matter, the insula, and surrounding cortex (Dronkers et al., 2007). More striking, neurosurgical resection of Broca's area alone, sparing these neighboring structures, often produces only transient speech deficits that resolve within months. One computer engineer returned to professional work after tumor removal destroyed his entire left inferior frontal gyrus. These cases suggested that Broca's area was neither necessary nor sufficient for speech production.

Direct cortical recordings delivered the final surprise. Using ECoG during word production, Flinker and colleagues (2015) found that while motor cortex activated robustly during speech, Broca's area was "surprisingly silent" during actual articulation. It activated earlier, during preparation, coordinating information between temporal and motor regions, but the execution of speech happened elsewhere.

The Target

The region that does activate during speech execution, and yields the signals most useful for BCI decoding, is the ventral sensorimotor cortex (vSMC), specifically the ventral precentral gyrus encompassing area 6v (ventral premotor cortex) and adjacent M1v (primary motor cortex). This strip of tissue, tucked along the Sylvian fissure, controls the lips, tongue, jaw, and larynx.

Chang's group at UCSF established the foundational map in 2013, using high-density ECoG during syllable production to reveal somatotopic organization of speech articulators across vSMC. Crucially, they found that articulator representations partially overlap at individual electrodes and coordinate temporally during speech, exactly the kind of signal structure amenable to decoding.

When Willett and colleagues at Stanford (2023) implanted intracortical arrays in both area 6v and area 44 for their high-performance speech BCI, the comparison was decisive. The area 6v arrays proved far more informative than the area 44 (Broca's) arrays, providing the neural substrate for achieving 62 words per minute at 9.1% word error rate. The study found that speech articulators were "intermixed at the single-electrode level" within the 3.2 × 3.2 mm area 6v arrays, all four articulator categories (lips, tongue, jaw, larynx) were represented even in this small patch. This spatial mixing is actually beneficial: it means accurate speech decoding is possible from a small number of electrodes covering limited cortex.

Motor Cortex Beats the "Language" Areas

The vSMC represents the actual kinematic trajectories of speech articulators, the movements of tongue position, lip aperture, and laryngeal state that produce phonemes. This is a more direct signal than the abstract phonological codes in Broca's area or the acoustic representations in superior temporal gyrus.

Perhaps the most encouraging finding for BCI development is that articulatory representations in vSMC persist years after someone loses the ability to speak. Willett et al. demonstrated that their participant, who had been unable to speak intelligibly for years due to ALS, still had detailed phoneme representations in area 6v that correlated strongly with articulatory movements measured in able-bodied speakers. The motor plans for speech survive even without execution.

Herff and colleagues (2019) systematically compared speech reconstruction across inferior frontal gyrus, premotor cortex, and motor cortex. The motor cortex provided substantially more information than either of the other regions, activity there enabled intelligible speech synthesis while the others did not.

Speech unfolds rapidly, with phonemes lasting tens of milliseconds. The vSMC generates temporally precise signals locked to articulation timing, while higher-order areas like Broca's operate on slower, more variable timescales related to planning rather than execution.

Regions Tried that Disappoint

Several brain regions, though important for speech and language, proved less useful for BCI decoding. These are described below.

Despite its reputation, area 44 contributes less decodable information than motor cortex. Current understanding places Broca's area in a coordinating role, marshaling information between temporal and motor systems, handling syntactic complexity, and sequencing phonological units, rather than directly encoding articulatory movements. It is active during speech preparation but quiet during execution.

STG (superior temporal gyrus) excels at the auditory representation of speech sounds, encoding phonetic features like place of articulation and voicing. (Mesgarani et al., 2014) showed exquisite phoneme selectivity in STG during listening. But for production BCIs, this region presents challenges: its activity reflects auditory processing rather than motor commands, and in individuals who cannot speak, there's no auditory feedback to drive these representations.

The hand and arm regions of motor cortex, though easier to access surgically, lack the somatotopic proximity to speech articulators. BCIs targeting these regions have succeeded for cursor control and typing but cannot tap the rich articulator representations needed for natural speech decoding.

Connected to speech networks via the superior longitudinal fasciculus, the supramarginal gyrus in the parietal region plays supporting roles in phonological processing. Some lesion studies associate it with Broca's aphasia when damaged alongside frontal regions, but it doesn't provide the direct articulatory signals useful for real-time decoding.

Performance Comparison

Both ECoG and intracortical approaches have converged on the same narrow strip of cortex. UCSF's ECoG work, Stanford's Utah arrays, and emerging high-density systems like Precision Neuroscience's Layer 7 all target the ventral precentral gyrus, the region where phonemes meet movement.

A 256-electrode ECoG array over the wrong cortex will underperform a single 96-channel Utah array in the right location. Speech BCIs live or die by their proximity to ventral sensorimotor cortex.

Head-to-Head Performance

| System | Electrode Type | Channels | Best Accuracy | Speed | Vocabulary | Calibration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanford/BrainGate (Willett 2023) | Intracortical (Utah) | 256 | 90.9% / 76.2% | 62 wpm | 50 / 125k words | Hours |

| UC Davis/BrainGate (Card et al. 2024) | Intracortical (Utah) | 256 | 99.6% / 97.5% | 32 wpm | 50 / 125k words | 30 min |

| UCSF (Moses 2021) | Subdural ECoG | 128 | 74.4% | 15 wpm | 50 words | Weeks |

| UCSF (Metzger 2023) | Subdural ECoG | 253 | 75% | 78 wpm | 1,024 words | Days |

| UCSF Streaming (Littlejohn 2025) | Subdural ECoG | 253 | ~75% | Real-time | 1,024 words | Days |

Intracortical arrays currently achieve the highest accuracy, particularly for large vocabularies. The single-neuron resolution enables finer discrimination between similar phonemes. The UC Davis system's 97.5% accuracy on a 125,000-word vocabulary represents the field's best result.

High-density ECoG achieves the fastest decoding speeds (78 wpm vs. 32–62 wpm for intracortical) and has demonstrated better long-term signal stability. The UCSF streaming system solved the latency problem that previously favored text-based output.

The tradeoff is surgical risk versus signal quality. Intracortical arrays penetrate brain tissue and face gradual degradation from glial scarring; ECoG sits on the surface with less tissue disruption but captures population-level rather than single-neuron activity.

Both approaches have now demonstrated real-world, everyday use by participants with severe paralysis. The choice between them may ultimately depend on individual patient factors such as disease progression, life expectancy, and tolerance for surgical risk, rather than a universal "best" option.

References

- Bundy, D., et al. (2014). Characterization of the effects of the human dura on macro- and micro-electrocorticographic recordings. Journal of Neural Engineering, 11(1), 016006. doi:10.1088/1741-2560/11/1/016006

- Liu, D., et al. (2024). Reclaiming hand functions after complete spinal cord injury with epidural brain-computer interface. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2024.09.05.24313041

- Yao, R., et al. (2025). Fine grained two-dimensional cursor control with epidural minimally invasive brain-computer interface. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2025.10.06.25337264

- Mitchell, P., et al. (2023). Assessment of safety of a fully implanted endovascular brain-computer interface for severe paralysis in 4 patients: the Stentrode with thought-controlled digital switch (SWITCH) study. JAMA Neurology, 80(3), 270-278. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.4847

- Levy, E., et al. (2024). COMMAND: early safety and feasibility results of a permanently implanted endovascular brain-computer interface. The Lancet Neurology, 23(8), 791-800. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00212-3

- Moses, D., et al. (2021). Neuroprosthesis for decoding speech in a paralyzed person with anarthria. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(3), 217-227. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2027540

- Metzger, S., et al. (2023). A high-performance neuroprosthesis for speech decoding and avatar control. Nature, 620, 1037-1046. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06443-4

- Chartier, J., Anumanchipalli, G., Johnson, K., & Chang, E. (2018). Encoding of articulatory kinematic trajectories in human speech sensorimotor cortex. Neuron, 98(5), 1042-1054.e4. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.04.031

- Littlejohn, K., Leung, E., Shevidi, S., Moses, D., Anumanchipalli, G., & Chang, E. (2025). Real-time synthesis of imagined speech processes with brain-computer interfaces. Nature Neuroscience, 28, 443-450. doi:10.1038/s41593-024-01836-y

- Luo, S., et al. (2023). Stable decoding from a speech BCI enables control for an individual with ALS without recalibration for 3 months. Advanced Science, 10(35), e2304853. doi:10.1002/advs.202304853

- Hahn, N., et al. (2025). Signal stability and decoder performance in long-term intracortical brain-computer interface use. Journal of Neural Engineering, 22(1), 016024. doi:10.1088/1741-2552/ad9f7a

- Willett, F., et al. (2023). A high-performance speech neuroprosthesis. Nature, 620, 1031-1036. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06377-x

- Fan, C., et al. (2025). Plug-and-play stability for intracortical brain-computer interfaces: a one-year demonstration of seamless brain-to-text communication. Nature, 629, 568-575. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-08611-2

- Simeral, J., et al. (2024). Home use of a percutaneous wireless intracortical brain-computer interface by individuals with tetraplegia. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 71(4), 1214-1227. doi:10.1109/TBME.2023.3334752

- Dronkers, N., Plaisant, O., Iba-Zizen, M., & Cabanis, E. (2007). Paul Broca's historic cases: high resolution MR imaging of the brains of Leborgne and Lelong. Brain, 130(5), 1432-1441. doi:10.1093/brain/awm042

- Mesgarani, N., Cheung, C., Johnson, K., & Chang, E. (2014). Phonetic feature encoding in human superior temporal gyrus. Science, 343(6174), 1006-1010. doi:10.1126/science.1245994